Martin Heng: Advocating for Accessible Tourism

- Team

- Jun, 20, 2024

- Interviews

- No Comments

Martin Heng: Advocating for Accessible Tourism

Martin Heng is a highly respected advocate for accessible travel, drawing on a rich background of professional experience and personal resilience. Born in Birmingham, UK, Martin holds a BA and MA in English literature from Cambridge University and an MA in Communications from RMIT University, Melbourne. In 1987, he left England and spent a decade living, working, and traveling around the globe before migrating to Australia in 1997.

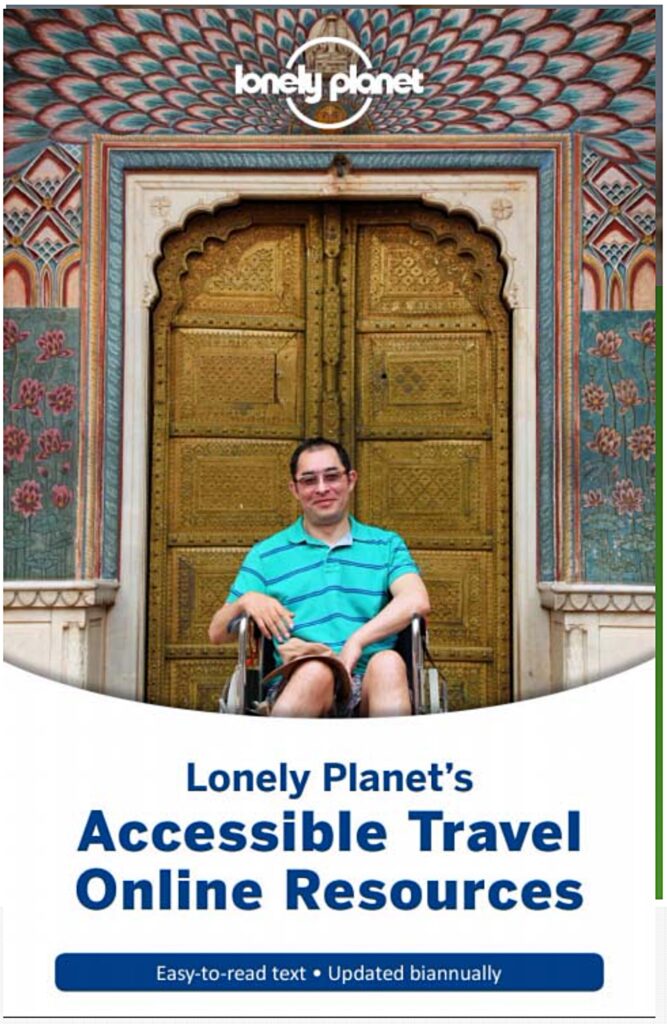

Martin joined Lonely Planet in 1999 and worked in various influential roles, including Editorial Manager. His career took an unexpected turn when a bicycle accident in 2010 left him a quadriplegic. Embracing this new reality, he became Lonely Planet’s Accessible Travel Manager & Editorial Adviser from 2013 to 2020. During this period, he published numerous accessible travel titles, including the world’s largest collection of Accessible Travel Online Resources and an Accessible Travel Phrasebook featuring disability-specific words and phrases in 35 languages.

Since 2014, Martin has been a prominent speaker at global travel conferences, including several UNWTO events. He also chairs the board of IDEAS, a nonprofit providing advocacy services for disability communities in Australia, and serves on the Victorian Disability Advisory Council. Additionally, he is a founding member of the Spinal Cord Injury Network of Professionals in Melbourne.

In this interview, Martin shares his insights on:

- His Journey and Career: From his global travels and time at Lonely Planet to his transition to accessible travel advocacy after his accident.

- Challenges in Accessible Travel: The main barriers faced by travellers with disabilities and how these have shaped his views on accessible tourism.

- Opportunities for Businesses: The market potential businesses miss by not focusing on accessible tourism, with examples of companies that excel in this area.

- Practical Steps for Accessibility: Advice for businesses on improving accessibility with minimal costs, emphasising the importance of accurate information and staff training.

- Innovations and the Future of Accessible Tourism: Innovative solutions and technologies supporting accessible travel, and the evolving role of government policy.

Can you tell us about your journey and how you became an advocate of accessible travel?

Martin Heng: I’ve always been a traveler. I started traveling at 16, riding a bicycle from Birmingham to northern France. In 1987, I left England to travel and spent ten years in Asia before moving to Australia. I joined Lonely Planet in 1999 and worked there until I had an accident in 2010 that left me quadriplegic. During my rehab, I started thinking about traveling with a disability and discovered the field of accessible travel. I learned a lot and became the accessible travel manager at Lonely Planet in 2014.

That sounds like an incredible journey. Can you elaborate more on your time at Lonely Planet and how your role evolved there?

Martin Heng: Sure. At Lonely Planet, I started as a managing editor and later held positions as a commissioning editor, publishing manager, and finally editorial manager. I had quite a responsible position until my accident. After my rehab, when I started thinking about travel with a disability, I realised how little I knew about it despite having a brother who was a quadriplegic. It was a humbling experience, and I spent a year researching and connecting with mentors in the field of accessible travel. When I returned to work, Lonely Planet was very supportive and created the role of accessible travel manager for me in 2014. Since then, I’ve been advocating for accessible travel both within and outside the company.

While you now need special accessible help, what are the biggest challenges you have faced as a traveler, and how have these shaped your view of accessible tourism?

Martin Heng: The biggest challenge is the lack of information. People with disabilities need verified, up-to-date, accurate information for planning. Another issue is the lack of consistency in the meaning of „accessible“, especially in hotel rooms and bathrooms. For example, in the UK, an „accessible“ room might have a bathtub with grab rails, which isn’t helpful for someone who needs a roll-in shower. Attitude is also a barrier; people with disabilities are often ignored or assumed to have no agency. Physical barriers can be overcome with flexibility and assistance, but information and attitude are crucial.

Can you share more about the physical barriers and how you’ve managed to overcome them during your travels?

Martin Heng: Physical barriers are a significant challenge, especially in developing countries where infrastructure might not be as developed. For instance, when I traveled to India, there were no wheelchair-accessible vehicles available, so we had to get creative. I would get into a regular van with assistance, and we hired locals to help lift my wheelchair into the vehicle. Similarly, in places where there were no accessible paths, I relied on my support worker and local helpers to carry me and my wheelchair. Flexibility and a willingness to adapt are key. There are also innovations like the TrailRider or the Joëlette that allow people with disabilities to go trekking, showing that physical barriers can often be overcome with the right tools and mindset.

It seems like making tourism more accessible isn’t that difficult with the right information and attitude. What are the opportunities businesses miss by not focusing on accessible tourism?

Martin Heng: Approximately 20% of the global population has a disability, representing a significant market. Studies show that the disability community has $8 trillion a year in disposable income, increasing to $13 trillion when including family and friends. Businesses not catering to people with disabilities miss out on this substantial market. Additionally, people with disabilities tend to stay longer, spend more, and are more loyal, often traveling in off-seasons. For example, a study by Visit England found that the Purple Pound, which is the spending power of people with disabilities, is worth about 14.6 billion pounds annually. The Open Doors Organization in the US estimated that people with disabilities spent $58.7 billion on travel in 2018 alone. This is a huge market that businesses can’t afford to ignore.

Do you have examples of businesses focusing on accessible tourism and what others can learn from them?

Martin Heng: One example is Skyrail in Cairns, Australia. They provide clear accessibility information on their website and are accommodating. They slowed the gondola ride, folded my wheelchair, and ensured assistance at each station. Their disability confidence and willingness to listen made a potentially inaccessible experience seamless. Another example is the Park Hyatt in Melbourne. They offer a range of accessible rooms and have staff trained to assist guests with various disabilities. They even provide a detailed accessibility guide on their website, which is extremely helpful. These businesses show that being open, flexible, and proactive in providing information and assistance can make a significant difference.

What advice would you give to businesses wanting to start focusing on accessible tourism without major reconstruction?

Martin Heng: First, create an accessibility guide detailing your facilities and how to reach your venue. This requires only time and effort. Look for low-hanging fruit, like adding a portable ramp or providing a service dog area. Train customer-facing staff to understand your venue’s accessibility features and address common barriers. This knowledge helps in accurately answering questions from people with disabilities. Also, consider implementing simple solutions like ensuring clear pathways and reducing clutter. These steps can significantly improve accessibility without a large investment.

Often, businesses cite a lack of funds for major accessibility changes. How can they start improving accessibility with minimal costs?

Martin Heng: Nowhere will ever be 100% accessible, so start with what you have. An accessibility guide is a significant step and costs nothing. Small changes, like decluttering pathways and providing accessible reception tables, are low-cost but impactful. Removing obstacles and ensuring clear pathways can help people with various disabilities. For example, adding a sign for a service dog toileting area or a portable ramp for entrance steps can make a big difference at a minimal cost. Additionally, having a seat and lower table at reception can assist those who cannot stand for long or reach high counters. These are simple yet effective ways to start.

Is there a need for specialised training for staff to better serve customers with disabilities?

Martin Heng: Disability awareness training is useful for understanding different disabilities and appropriate interactions. Training in the specific features and barriers of your venue is crucial. Knowing whether there’s a step at the entrance or accessible facilities can make a big difference. Additionally, training should cover the various types of disabilities, from physical to sensory and cognitive, and the specific needs associated with each. This comprehensive understanding enables staff to provide better service and make the venue more welcoming. For example, knowing how to guide someone with low vision or how to communicate effectively with someone who is deaf can greatly enhance the customer experience.

What do you think about the role of education in improving accessibility awareness?

Martin Heng: Education plays a critical role. Including accessibility in tourism and hospitality courses can significantly raise awareness. Portugal, for instance, has incorporated accessible tourism as a unit in their tourism courses, which is a great step forward. Educational institutions should ensure that future professionals are equipped with the knowledge and skills to cater to people with disabilities. This can help create a more inclusive industry from the ground up. By integrating these concepts into the curriculum, we can foster a new generation of professionals who prioritise accessibility in their planning and operations.

How can existing businesses get the necessary training for their staff?

Martin Heng: Many NGOs offer disability awareness training. Access consultants can assess physical infrastructure and provide recommendations. These consultants measure various aspects like door widths and toilet seat heights to ensure accessibility. Combining awareness training with practical assessments helps businesses understand and address both attitudinal and physical barriers effectively. Additionally, some government and industry bodies offer resources and training programs specifically designed to improve accessibility in tourism and hospitality.

Thank you, Martin. This has been very insightful. Any final thoughts?

Martin Heng: Businesses should view accessibility as a win-win situation. It’s not just the right thing to do; it’s good for business. Increased accessibility benefits both the business and its customers. By making these changes, businesses can tap into a loyal and growing market segment, ensuring their sustainability and success in the future. It’s about creating an inclusive environment where everyone feels welcome and valued.